Demo: First Impressions

- Page published

- 2024-07-05

- World

-

Enotria: the Last Song

Enotria: the Last Song

This article is a reaction to the demo, as published by the developer a few months before the game’s full release: it certainly mentions things that will no longer hold true in the full game.

“Set in a beautiful sun-lit world inspired by Italian folklore”. Those were enough words in the marketing blurb of Enotria to get me soyfacing and downloading the demo.

It is too rare to see games set on our planet that dare to leave the safe confines of Central Turtle Island, Dai Nippon Teikoku, or Vichy France.

Jyamma Games: the developer is an unknown quantity. I looked them up to figure out whether they were Italian or not, and thus, decide whether to soyface to a greater or lesser extent.

And indeed, they are from Milano!

Bellissimo and arrivederci or something, i don’t know any Italian at all, even if i live just next to them.

Before making Enotria, Jyamma Games made a few mobile games that have, to put it as politely as possible, a texture more fashioned by late capitalism than love.

I should do my best to avoid passing judgement about the ways they bootstraped themselves. However, my download is only 83% done, and i am running out of things to say before i try the actual game. Thus, maybe i shall judge. I am looking at a cartoony microtransactions-heavy mobile game entirely at odds with the sort of game Enotria purports to be, passing judgement as hard as i can.

Downloading 11 GB takes a little while, even at French Fiber speeds. It uses Unreal Engine, which isn’t known for its aggressive download size optimization.

Once installed, the settings offered are truly minimal, but they include a colorblindness filter, which is always good to see, if only because it means the developers probably paid attention to other forms of accessibility that require no user-facing option.

The settings also indicate that voice acting is only available in English, with no option to change it to Italian.

I was reconsidering my soyfacing, until noticing a community manager from Jyamma Games confirmed the full version will have Italian dubbing. Autoimprenditorialità and caratterologicamente! I do not know what those words mean by the way, i just like it when game characters speak the language of their country.

Having a mild auditory processing disorder, i require subtitles for everything, so i always prefer to hear the local version juxtaposed to the text. Though sadly, a few enemies utter inconsequential lines during combat, which i found no option to have subtitled.

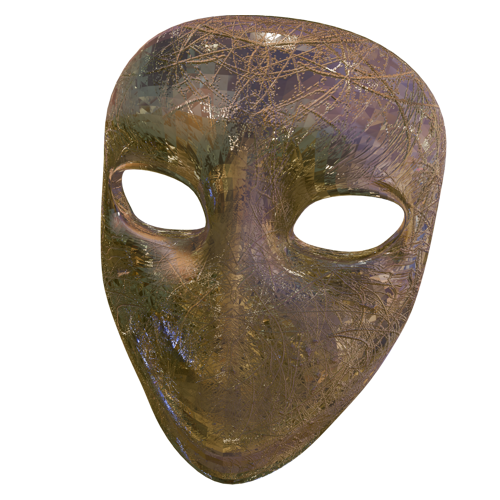

The Mask of Change, your character, is canonically addressed with gender-neutral pronouns: before wearing a mask taken from an enemy, they are but a wooden mannequin.

Inspired by the Commedia dell’arte, the mask embodies an archetypal character, not necessarily of the gender of the actor who dons it.

The first boss didn’t survive long enough for me to take cool screenshots.

The user interface layout reflows depending on your input device. Since my controller’s screenshot button emulates a keyboard key, you’re seeing the keyboard interface in some of my pictures.

Highlighting the developer’s attention to detail, there is even a tutorial message that will change its text on-the-fly to include information only relevant to controller users.

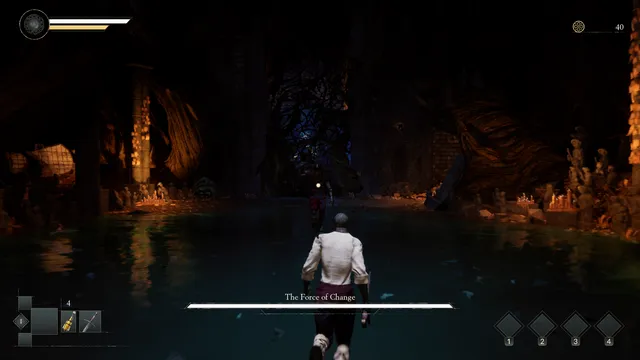

After a minimal introduction, my character awakes in the Caverna del Tutorial, and they quickly find themself pitted against a quick and painless little boss.

This fight is our first introduction to Aram Shabazians’ fantastic soundtrack for the game. Composer and audio director for the game both, his songs make Italian Folk music the star of the show, avoiding the hollow blasts of orchestral bombast de rigueur for the genre, allowing instead the melodies to pierce through during the fights.

Why not click to listen to this banger as you continue reading?

After the boss fight, the tutorial promptly wraps up, and the game gives you a large quantity of items to play with—chances are, many more than you’d get in the full game.

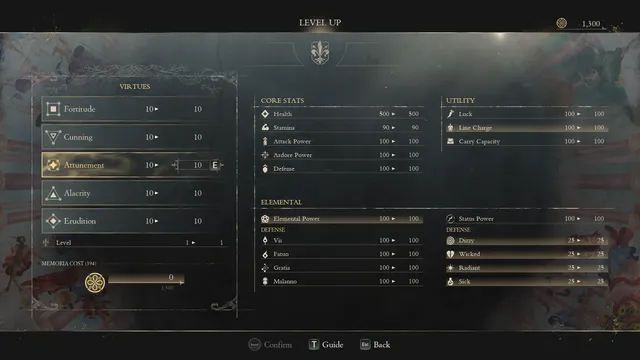

Each attribute to the left influences stats to the right.

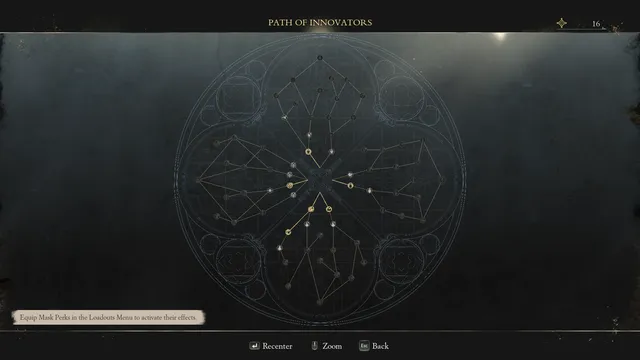

The Path of Innovators is slightly less intimidating than the Path of Exile.

Your equipment tab slots can be changed anytime, but the role tab slots, only at a checkpoint.

With those items, you can start customizing your build. It is defined by the interaction of many equipment choices, and Enotria exposes them all from the start.

Despite their large amount, the system feels remarkably elegant and easy to understand, fitting comfortably in only three screens available from the checkpoints.

We have the usual attributes to Level Up, named Fortitude, Cunning, Attunement, Alacrity, and Erudition, which influence stats and requirements—the usual.

It follows the trend of using an idiosyncratic naming scheme to make it clear it follows its own logic, as games such as Wo Long or Thymesia do, but seems to have a mandatory non-differentiating stat in the form of Fortitude, much like Elden Ring requiring a substantial Vigor investment on every build.

The perks tree, named the Path of Innovators, allows you to buy passives you can equip, using a currency mostly obtained by exploring the stages.

The last screen, Loadouts, is the most interesting one.

You are defined by your Role—first and foremost your Mask, which has bonuses and sometimes drawbacks.

To this is added an Aspect, which alters your attributes positively and negatively, but increases your stat density as a whole, and has additional special effects.

You then pick Perks from the tree, the masks i found having six slots for those. While none of the unlockable perks felt build-defining, this seems more the sort of game where you have a lot of avenues to stack up small modifiers that work well together.

Then, you can pick two weapons that you can swap but not dual-wield, an accessory, four special attacks named Mask lines, and six quick item slots.

And there are three loadout slots in total, that you can swap anytime. That means 6 weapons available at any time, and three belts of items.

While i found little reason to make use of more than a single loadout in the demo, hopefully, the full game will offer both the tools and the challenges to encourage their use.

Many aspects of your build are about balancing tradeoffs, to the point that the four status effects that can affect you are neither pure buffs nor ailments, but a combination of both: you have items to both inflict them upon yourself or to cure them.

In addition to this, weapon upgrades are refundable: you can simply remove the upgrade stones you hammered into them, using Science. Upgrading another weapon still requires expending souls (here rebranded Memoria), but it means you’re never locked into a bad weapon because you can’t find enough upgrades to use something else.

Finally emerging out of the menu, i step into the sun.

The sunflowers rotate to face you. Except for a single bugged sunflower that rotates at random as you move.

The graphics have that Unreal Engine Default Settings tinge: smeary and blurry, as if they were rendered at half resolution, with poor frame pacing, but beautifully lit.

Even on a system that outperforms the recommended hardware configuration, i found myself having to moderate the graphics settings to keep a decent 60 FPS-ish pace without microstutters.

The first stage makes great use of light and shadow, but the effort put into environment art takes a nosedive in the second stage, almost entirely avoiding shadow-casting lights even in its interiors.

I hope you like motion blur and camera shake.

The game plays as if in slow motion: windups take their sweet time. With a longsword, a running R1 attack feels slower than stopping sprinting before swinging. The ultra greatsword moves come out so slow, you can only hope to punish a whiff after baiting an opening.

But as slow as it might be, after a while, you adapt to its theatrical rhythm.

The game frequently takes over your camera to apply its own bias or rotation speed modifier to it, even when you do things such as opening doors or resting at a checkpoint, increasing the feeling of sluggish movement.

The one animation that comes out instantly is the Parry.

Because it’s one of those games.

Almost everything can be parried, and the parry windows are very generous.

Parrying a crossbow from a distance.

Even when faced with enemies who shoot crossbows at you, the best way to deal with them is to simply parry their bolt—which will actually stagger them from a distance, allowing you to go in for a grapple finisher, or leaving them neutralized long enough for you to kill another enemy.

Later on, the game introduces enemies who shoot homing projectiles with excellent tracking, following you even behind cover: parrying is the only reasonable option to deal with those, and you can even parry shots coming at you from behind.

Going for finishers is an important part of the fight mechanics, building up a posture gauge named Unraveling. Only enemies do have such a gauge, it is not a symmetrical system as in Sekiro. You can build up this gauge through parries and regular attacks, and with some perks, you can even build it up by dodging.

To actually trigger a finisher on an enemy opened up to them can be a little unreliable, however. I found it necessary to entirely stop all movement for a split second before initiating the grapple, otherwise, the window of opportunity would be wasted by a normal attack.

While finishers do hefty damage, a fully parry-centric gameplay doesn’t seem as strictly enforced as in Lies of P, as much as it is made a very attractive tool for any build.

Fools, imbeciles, and people of that nature might suggest that another option to compensate for the slow attack speed of an ultra greatsword would have been for me to swap to a faster off-hand weapon for some encounters.

Obviously, i would never do such a thing. Being a DEX build your first time through a game is morally abhorrent.

Using an ultra greatsword, parrying seemed to be the only way to deal with some regular enemies, such as a hammer bro whose attacks would always interrupt mine, and come out too fast for me to land a single R1 between combos.

The game doesn’t appear to have a poise system, nor do heavy weapons have innate hyper armor: whether your moves get interrupted or not mostly seem an intrinsic property of individual enemy attacks.

The game teases you with distant loot you can’t obtain in the demo. Once the full game is out, it’d be interesting to explore how much of the actual game made it into the demo, merely made physically inaccessible without going out-of-bounds.

The Mask of Change can restore this crumbled bridge by invoking the power of pressing the action button in front of a conspicuous interaction marker.

While this system is advertised as a headline feature, it feels more like a mild narrative flavor additive.

The two available stages have that classic “door does not open from this side” and “how the hell am i even supposed to jump on this” compact construction, with branching paths and one-way shortcuts folding back on themselves.

As you explore, you’ll notice Autoloot, enabled by default. It is a peculiar choice, and one that doesn’t actually free a controller bind, as treasure chests still need to be opened manually, but shinies outside containers give your kleptomania no pause.

A quality of life choice in a genre that prefers friction: it feels odd, and once you get used to it, you don’t want to disable it, but still wonder if it was the right choice.

Autoloot will even pick up critical upgrades with nary a notification, and apply them automatically: without fanfare, you suddenly find yourself with an upgraded healing item, or more charges of it. You might not even remember when or where you picked up the upgrades.

As per frequent genre custom, no music accompanies exploration, but the audioscapes feel less naturalistic than the norm, with many non-diegetic sounds, a bit reminiscent of Lords of the Fallen (2023)’s audio direction.

In a particular section, music is heard in a street party, a masked flutist dancing among peers. Yet, even if you slaughter all the celebrants, the music continues, and no musicians are to be found, creating an eerie feel.

A few streets away, Pulcinella strums the same melody in a quieter reprise. He stands before a church, its inside walls covered in decaying frescoes where the face of every human depicted has been scratched out.

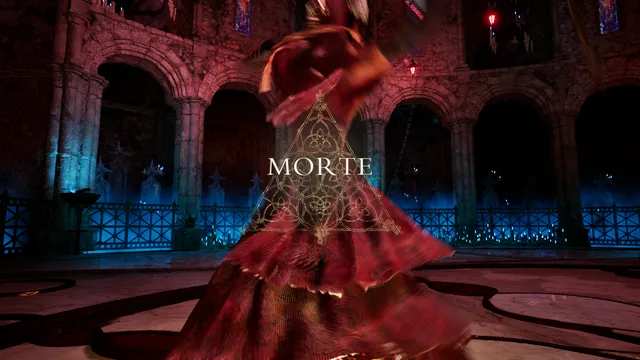

Inside the church stands the first real roadblock: Curtis, Prince of Laughter. As often with the first real boss, he’s a groove check who will take a few attempts on your first try, then go down very easily on subsequent attempts: he simply asks if you understand how the game ticks yet.

And the game ticks by parrying.

With the generous timing windows, realtively easy to read windup animations, and the arena obstacles making dodges unattractive, it teaches you to reach for a parry where you’d normally roll.

Curtis intuitively feels like a strange name in this universe, doesn’t it?

He isn’t a character from the Commedia dell’arte like Pulcinella: he is Antonio de Curtis, stage name Totò, a famous actor born at the end of the 19th century.

Learning of this fact truly makes you wonder what’s going on with the story, and how they made all those ideas fit together, but you’ll wonder to no avail. The items you can find are tight-lipped on narrative context. It seems the story fragments you collect are hidden in the Compendium menu, grayed out in the demo.

Exiting the church from the back leads you to black skies, just a few steps away from the sunny village. The game operates on the mythical level, a dream-like experience not too concerned with such trifling physical details.

While the second stage remains decently constructed in terms of level design, as i mentioned, the art quality takes a very predictable hit. It’s likely the first stage is the most beautiful in store for us. Still, obviously, the fantastic art direction takes precedence over the technical demerits.

There has been a fair amount of critique issued towards the game’s perceived jank. It is excessive. Every new game in the genre will see new players trying to play the game exactly like they play Dark Souls, finding it’s not working out after their tenth attempt at a boss, refusing to learn anything from their failures, refusing to adapt to the pace set by the game, refusing to use any of the tools at their disposal, and choosing to instead demand the developers fix their game to become exactly like Dark Souls.

And the last boss of the demo, certainly, will kick your teeth in ten times. It represents a huge bump in difficulty, probably with cranked up stats for the demo. Your opponent gives you little margin of error, but still allows multiple approaches.

After accepting parrying everything was just not working out for me, i instead favored dodging and punishing specific attacks with a charged ultra greatsword hit, staggering the boss long enough for a follow-up hit, then using a Mask Line special attack when available.

By the point you reach this boss, the system makes sense and the rhythm feels right.

There’s idiosyncracies and rough edges: Enotria has plenty, and we can work with those.

There’s jank and bugs: on this front, my complaints are few; my biggest frustration were wasting so many grapple windows because they’re too touchy to trigger predictably, and lock-on switching feeling unreliable.

We’re blessed to see many developers the world over try their hand at the formula, bring new systems to the conversation, and create something worth playing on their first attempt. Enotria is clearly the work of people who have though critically long and hard about the genre, and while their ideas might not end up landing, i have high hopes for the full game.