Overview

- Page published

- 2024-07-26

- World

-

Code Vein

Code Vein

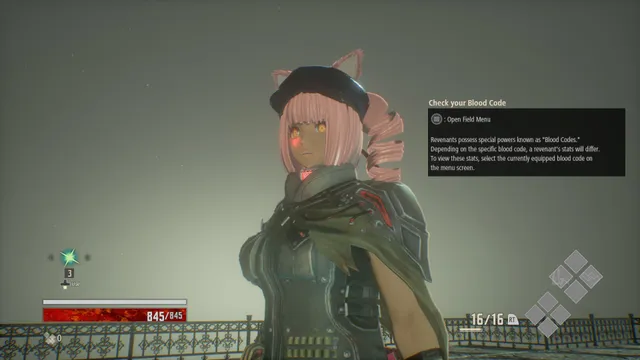

Meet Boobies, the heroine of Code Vein. She does not have the option to wear legwear in a symmetrical fashion.

I am the last person who’d criticize a game for sexualized aesthetics, but the adventures of Boobies were not fun.

The character creation system might be what initially sold me on the game. I certainly spent a while with it starting the game, thinking i’d adjust my looks all the time.

The customization options were truly unmatched in 2019. A huge assortment of accessories, freely positionable on your character.

And seven outfits.

Seven premade outfits (plus a joke one that’s just a towel). All you can really do with them is change their colors, and remove layers.

For example, in the short shorts and underboob crop top combo, you can remove the top to reveal the underboobier bra underneath.

After my first 2019 playthrough at release, Shift patched in an option to conceal the Blood Veils worn over your outfit. As this article uses pictures from a recent partial playthrough, they won’t be seen in the screenshots.

And all the customization amounts to very little in the first place: most of the game is played with a gas mask and an overcoat that will clash with your fashion choices.

The men might have more than seven outfits. Or fewer. I have not tried to make one, as playing a male character in an anime game is an even bigger faux pas than playing as a DEX build.

I took 499 other photos like these. Would you like to see them? Yes you would? Good.

Is it unfair that i start this overview by discussing the fashion, before i even discuss the gameplay? Well, dear reader, Code Vein is all about having priorities. And its priority is telling a story with sexy anime girls.

The developer, Shift, was previously responsible for two God Eater games, which follow the Monster Hunter formula.

Interestingly, Monster Hunter already met Demon’s Souls once, to mixed reactions, when Tomohiro Shibuya, chief designer of the former, co-directed Dark Souls II.

While Code Vein has narrative connections and cameos from God Eater, the gameplay doesn’t bring in the Monster Hunter vocabulary, and the universe is an entirely new narrative.

And what a narrative.

A small mercy of mediocre anime is that episodes last 20 minutes, and that there are only 13 of those, 26 if unlucky.

If your unexplainable, terrible life choices compel you to watch a cartoon such as I Got Run Over By a Pack of Wild Elephants and Now I Have Been Reincarnated As The Princess’ Sentient Motorcycle but it Turns Out the Princess is My Younger Sister until its bitter end (which i shall not spoil), while you will be a lesser person upon its completion, there is solace the hour of such completion is known in advance.

The theme of this cutscene is “Humanity” and “Hope”. Boobies is holding an item that will give humans hope.

Code Vein grants no such clemency. Cutscenes employ subtext, nuanced characterization, and narrative economy as little as possible, in favor of exposition, stated multiple times in a row to make sure you understand the themes of the story (power of friendship, what it means to be human, grieving about a little sister, grieving about an older sister, and things of that nature).

Characters reformulate their statements multiple times—be it about the bonds of friendship, about clinging to their humanity, over the grief of losing their family, or understanding a little sister’s sacrifice. Often, they mention the plot point in more than a single cutscene, to make a poignant point about what friends mean to them, how horrible it is to lose one’s humanity, and the pain of losing those whom you hold dear (especially siblings).

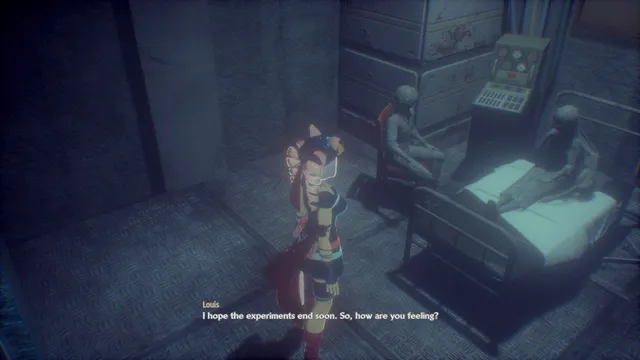

This one was about a bedridden girl suffering, as a boy suffers he has to see her suffer such suffering.

Cutscenes are but one of the game’s three main narrative forms: the second one is the walking tour. Entering copy-pasted mind palaces, the main character, Boobies, is prevented from running or proceeding before the voice actors are done narrating static dioramas about various themes (such as how important friends are to a character, losing grip on their humanity, and losing their sister in a tragedy). To endure them all will take almost 90 minutes. The one i found the most touching was probably the one where the younger sister dies.

You do not wish to rewatch a cutscene. The option, nonetheless, is offered.

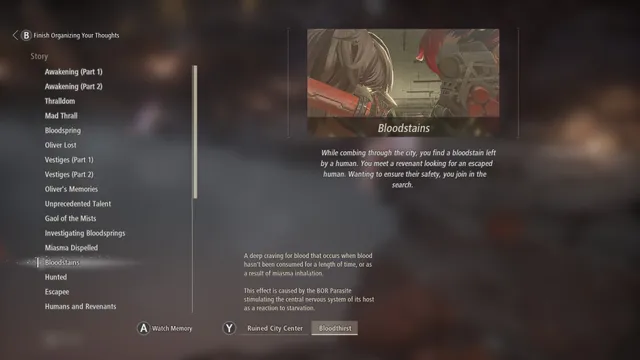

And the third narrative form, obviously, is the summary: despite the copious exposition overtaking the entire experience, the characters still fail to properly explain their universe. Thus, summaries remind you what happened, while explaining important keywords the cutscenes do not mention.

And i told you, i am the last person who’d criticize a game for sexualized aesthetics.

But the boys get to look cool while the girls get to wear torn clothes.

The only mode of eroticization the character designers know is the cutout: there is almost no female outfit to which someone hasn’t taken their scissors to haphazardly expose skin. One dress cut at the cleavage. One dress cut… under it. One dress that does does not enclose the back. Pants that do not enclose the side. Pants cut and kintsugi’d with lace. Even a cutout in a bikini top.

If you’re gonna make an obvious sex appeal game… Your portfolio of sexiness should be a bit more diversified than that of a fetish artist.

There is a Photo Mode in the game. Photo Mode is by far my favorite game feature to have emerged as a standard in the last decade! Shame there isn’t a single outfit worth photographying my character in.

And while the women breast boobily on-screen, their stories are always the same: they are the little sister who dies to remind an older brother what it means to be human and have friends.

A story like this is all right as part of a more balanced narrative.

But in Code Vein, the women’s stories always entail self-sacrifice for the character development of heroic men.

The rigid narrative enforcement of gender roles is a lot more bothersome than a few tits.

You might think it’s unfair i opened by talking about the story first, when we’re all here for the game systems, to compare its gameplay to other works in the genre.

Yet isn’t it fair to engage with Code Vein on its own terms? It aims to be a bad children’s anime first, a game only second.

While cobbled together from better narratives, the world it created is serviceable. A simple mythos of parasites creating immortal vampires who must feed or turn into monsters, despite my criticism it’s an ok reskin of dark sign, hollowing and estus flask, gets the job done.

In the hands of a team willing to axe the cutscenes and its cast of characters by 80%, to instead tell the story as you explore its environments, it could shine.

But its level design is even more sophomoric than its writing: it flips mazes of assets. Rocks, concrete pillars with exposed griders, destroyed cars, and tentacles are the only visual vocabulary for the entire experience. An aesthetic dictated entirely by absence of budget.

The static meshes are rotated into videogamey courses, without concern how they used to fit together as a world humans once lived in, and even much less concern how they fit together as a narrative experience.

Exploring the internals of the game with UE Viewer reveals how spartan the level design kits are.

The post-apocalyptic setting is taken as an excuse to assemble a world devoid of any object that might tell a story: blood tanks are the most narratively salient object you will ever encounter in this game about vampirism.

In fact, the folder structure of the game makes it clear most props with any shred of personality come from asset packs purchased from the Unreal Engine marketplace or Turbosquid.

But at least, the rocks and concrete walls are proudly made in-house by Shift.

The graphics were not the work of people who lack talent, mind. The lighting artists did a fantastic job. The anime shading is probably my favorite in terms of aesthetics and technical excellence both. It’s clearly the work of talented people given no budget, no time, no autonomy, mediocre art direction, and no reason to take their project seriously.

And there is no level you look forward to revisiting. They are, in order: the cave with concrete walls (purple), the ruined city of concrete walls, the red rocks covered in coral, the swamp of concrete walls, the FUCKING CATHEDRAL, the warzone of concrete walls, the rocks covered in snow, the cave with concrete walls (yellow), the ruined city of concrete walls (burning), the ruined city of concrete walls (buried in sand), the other cathedral, the ruined city of concrete walls (red), the castle of bricks, and the castle of bricks (covered in blood).

Many have loathsome gimmicks. One has water that slows you down. One causes you unavoidable fire damage as you explore. One drains your spellcasting abilities so much they become unusable. One spawns adds behind you, with no way to defuse the ambushes before they are hardcoded to happen via linked aggro.

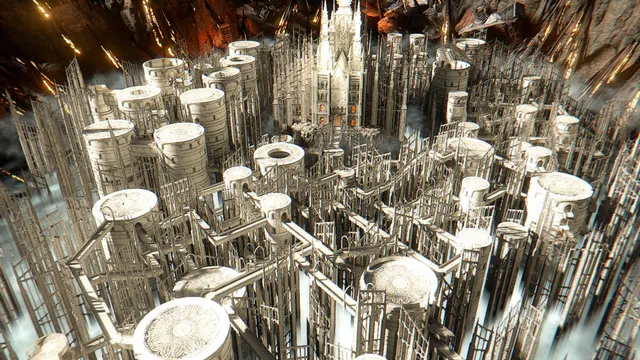

Boobies is approaching the FUCKING CATHEDRAL with Mia.

Reddit user Avallonkao used Unreal Engine cheat tools to snap this aerial view of the FUCKING CATHEDRAL.

Good Luck.

And the FUCKING CATHEDRAL. The FUCKING CATHEDRAL is comprised of ten different Anor Londo meshes colored white and rotated in the most incomprehensible game of Snake and Ladders possible, interspesed with extremely weak enemies. You will be lost and stuck for an hour or four.

After you finally find the exit, you will realize you only found a checkpoint to the next section hidden behind the FUCKING CATHEDRAL.

Then, later in the game, you must revisit the stage. Fuck you.

Sure, when you first enter the FUCKING CATHEDRAL, its stark design, contrasting with the drab rocks and concrete walls of the entire game, gives you a sense of vertigo; that sense quickly yields to a sense of WHERE THE FUCK DO I GO, as every single platform looks the same.

If you like rocks arranged in corridors, you will certainly enjoy visiting the Depths.

There are also bonus stages, that artfully kitbash Code Vein’s kits into daring combinations, such as ruined city of concrete walls (at night). Those areas are called the Depths. They are quick and painless linear micro-stages culminating in bosses. Datamining reveals they were originally intended to be procedurally generated, but Shift preferred instead a humanly-currated arrangement of rotated rock and concrete meshes.

The first map of the depths pits you against a boss who is a clone of Oliver Collins, the first boss you had encountered in the game a few minutes prior.

The second map of the depths pits you against a boss who is a clone of Oliver Collins, the first boss you had encountered in the game a few minutes prior.

This is the level of care put into Code Vein, which costs 50 euros.

For 25 euros more, you can purchase a DLC, which gives you 3 additional maps of the depths, pitting you against bosses from God Eater, Shift’s previous game. You will be done with those 3 maps in an hour (or 20 hours if you fight the bosses 100 times each to complete pointless challenges rewarding you useless trinkets).

Nice meme!

At this point, i am reminded that Mobygames cites 1,149 people in the end credits of that game.

This game has fewer environment static meshes than it has people in its credits roll.

Now, dear reader, you might think this might be about the point i should discuss the actual gameplay. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. Gameplay was clearly the last thing on Shift’s agenda, so we should match their pace.

First, may i say a few words about late capitalism? Many indie games have teams that number in the single digits, and achieve much greater feats of level design. What misattribution of human and monetary resources can possibly yield hours and hours of anime cinematics with an expansive cast of characters, yet set the story in the background of baby’s first asset flip?

Now, annoyed reader, you might think this might truly be the point i will finally actually discuss the goddamn gameplay.

Yeag ok. Let’s do that.

By far, Code Vein’s greatest contribution to the genre is decoupling level progression from stats: an innovation that is more of a reversion to the standard of JRPG, but one that enables instant respecs into various archetypes.

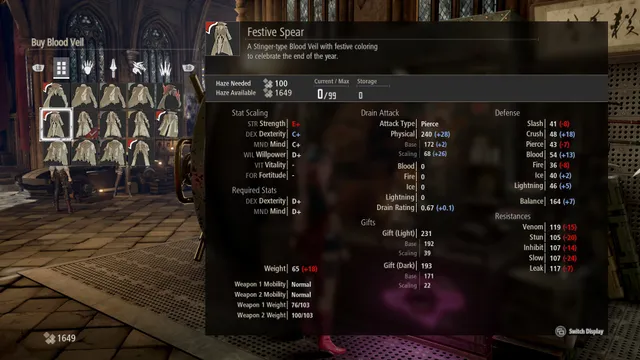

Your build fits on this single screen. Just add your level as a multiplier.

Your character is defined by her Blood Code. No—let’s be real, your character is gonna be a girl, so we’re not gonna do the inclusive language on that one. Your character is defined by her Blood Code: a bundle of stats sheet and unique skills, called Gifts.

Each Blood Code you make your own belongs to someone you met in your travels.

Each Blood Code comes with an average of 8 Gifts. Some Gifts are unique to their Blood Code, but most can be used on any Blood Code that meets the stats requirements. Such Gifts must generally be unlocked independently from the Blood Code. It entails spending resources, then spending more resources, or killing things with the Blood Code active.

You can change your Blood Code any time you want. However, once you unlock the best one, you won’t. After your first playthrough, the game rewards you with a Blood Code that makes all the others obsolete.

The skills are classified in 3 distinct categories: Passive Gifts (about 5% of skills), Active Gifts (about 15% of skills), and entirely pointless cruft nobody in their right mind would ever spend a slot on that was added to pad out the game (about 80% of skills).

Gifts are not intrinsic, they must be equiped manually. 4 slots for passives, 8 for actives.

To this, you add a Blood Veil armor, a generally ugly thing you can mercifully make invisible. It is responsible for your defense, of course, but also for your backstab, parry, and charged attack.

Each backstab is visually different, but functionally identical. While the game encourages levels of backstab fishing reminiscent of the first Dark Souls, the enemy hitboxes rarely match their animations: their true backside, as far as the game engine is concerned, might very well be their flank during certain attacks.

Each parry animation has different timings: there’s the one that’s too impractical to ever use, the one that’s too impractical to ever use, the one that’s too impractical to ever use, and the one that works on early game enemies.

And the charged attack is just that, its main focus being replenishing Ichor, the game’s mana system.

Do you like stats? Because we got stats.

None of this matters, however, as there are two Blood Veils that are obviously stronger than all the others, and are the best option on almost any build.

To the armor, add two Weapon slots, of course. Equipment has weight, but that of weapons is not cumulative: swapping weapons might change your mobility class.

You can upgrade Blood Veils with one out of twelve Transformations. Out of those twelve, Fortification is the strongest option in 80% of scenarios.

All three mobility classes seem viable, if only because the game does not feature any serious combat challenge. But as in many games in the genre, the fast agile dodge has a bit too much range for comfort: lateral dodges will often move to you places you didn’t expect, and leave you out of range to counterattack.

Pew pew.

There are only five classes of weapon in the game, but they have different movesets within a classes. The One-handed swords that you wield with one hand. The Two-handed swords that you still wield with one hand because you’re an anime girl. The Spears and Other Things mounted on a Stick for those who like range. The things that Bonk. And the most emblematic one: the Bayonet.

With the Bayonet, only one of your two attack buttons stabs: the other shoots. Shooting does good damage, but consumes Ichor. Ichor refills as you hit enemies: you rarely feel starved for it so long as you engage in melee, but to be a fully ranged fighter is difficult. Of course, there is system à la Bloodborne of Blood Bullets allowing you to trade Health for Ichor, if you can justify spending one Active Gift slot on it.

While there are at least a dozen weapons per class, there are only one or two best-in-slot options that overshadow all the others per class.

You can upgrade weapons with one out of twelve Transformations. Out of those twelve, Fortification is the strongest option in 98% of scenarios.

Ichor is mostly spent on Active Gifts: buffs and attack spells. It refills fast enough it’s easy to have buffs through entire stages, at least on some builds.

In pure design terms, this would be truly a beautiful system, if the game were balanced such that—if the game were balanced at all, really.

In practice, you use the obvious best Blood Code, the obvious best Blood Veil, your choice of one of the 8 best weapons, and before the boss room, you recite an interminable litany of buffs, you strut in, find an opening—then you one-shot the boss.

This is no hyperbole: every boss can and has been one-shot to the game’s 99,999 damage cap. It takes a fifty seconds recital first.

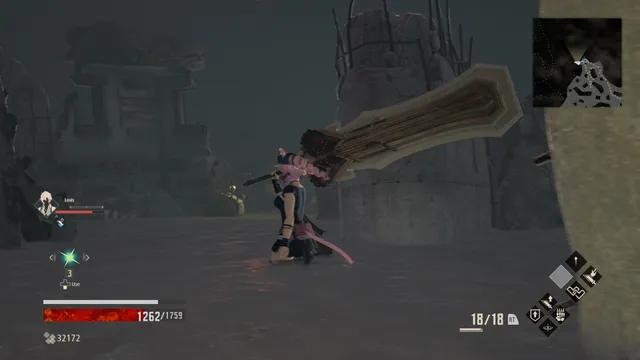

I would share more action shots than this, had the game had good action.

You rarely hear complaints that Code Vein is too unfair or too jank, even though it is both very unfair and very jank. That’s for a good reason: it’s too easy for it to matter. Nothing hits hard enough in the first playthrough that taking a few unfair hits matter. Nobody likes the game enough to play it again in NG+, when enemies start to two-shot you.

And if you ever struggle, your partner will revive you. Because you have a partner with you—at all times. Except for a short part of the tutorial, someone can always accompany you.

Every single action you take will be commented upon. If you run more than three meters ahead from them, they will chastise you for leaving them behind. If you find an item, they will not pass over this incident in silence. Sometimes, they will point things out on your map (as you do need a map to navigate its generic corridors of rocks without distinctive visual features). Eventually, you will reach for the menu option that makes them shut up forever.

Your allies are strong. Their attacks hit as hard as yours. Then they decide to pull a distant enemy, and refuse to fight while remaining stationary on a terrain feature causing damage over time.

Because you can always have an ally, the game is designed around it. You rarely fight solo enemies, always packs. With busy VFX, tight walls, and a camera system from before the genre standardized on my making your character invisible when too close to a wall… You have often have no idea what’s going on.

And your ally is not just content with blocking your path—often, blocking your dodge roll by standing behind you doing nothing. Your ally has the ability to displace you. If they bump into you, you get moved. While they do not have the ability to push you over a cliff, to simply have your character suddenly moved close to a pitfall always makes your heart race.

If one ally isn’t enough, you can have an additional online ally—in the very rare cases networking works. In typical Unreal Engine fashion, multiplayer is server-authoritative: as a cooperator, you will sometimes take damage from unseen sources, be yanked meters away after an internet hiccup, or be teleported over fatal pitfalls. Datamining revealed that PVP invasions were planned: a small mercy they were axed.

Getting a hit on the matchmaking screen is like winning the jackpot.

But of course, it doesn’t matter if it’s impossible to connect. At launch, on PC, the game used the player’s Steam Download Region to decide whom to matchmake to. Suffice to say, the regions being so many, the matchmaking pools were tiny, and the waits were long, despite a lot of players ingame. Nowadays, the issue has been fixed, but the playercounts are low, making random matchmaking just as difficult to find.

You can, of course, skip the ally. Given that you can one shot any boss, they aren’t that necessary. However, skipping the ally is nothing more than a deliberate hard mode: there is no rebalancing if you dismiss them.

It’s a shame Boobies is stuck in such a bad game.

Code Vein had two real contributions to the genre: first, by providing a constant AI ally, it provided an object lesson why you shouldn’t do that—a lesson that Team Ninja learned in Nioh 2 by keeping them a special treat and giving them a good AI, and a lesson they then proceeded to unlearn to make Stranger of Paradise: Final Fantasy Origin and Wo Long: Fallen Dynasty.

Its second contribution was to offer a system allowing constant respecs, proving it is workable, though it stops being useful once you earn the optimal Blood Code. Thymesia ran with this idea, making it easy to experiment with the skill tree, making some late game boss fights strongly favor specific builds.

That’s where my critique of the game mechanics end. For a game to deserve a sincere analysis of its systems, it needs to provide a meaningful and interesting challenge requiring me to engage with its systems.